from their about-section:

"Runme.org is a software art repository, launched in January 2003. It is an open, moderated database to which people are welcome to submit projects they consider to be interesting examples of software art.

Software art is an intersection of two almost non-overlapping realms: software and art. It has a different meaning and aura in each. Software art gets its lifeblood and its techniques from living software culture and represents approaches and strategies similar to those used in the art world.

Software culture lives on the Internet and is often presented through special sites called software repositories. Art is traditionally presented in festivals and exhibitions.

Software art on the one hand brings software culture into the art field, but on the other hand it extends art beyond institutions.

The aim of Runme.org is to create an exchange interface for artists and programmers which will work towards a contextualization of this new form of cultural activity. Runme.org welcomes projects regardless of the date and context of their creation. The repository is happy to host different kinds of projects - ranging from found, anonymous software art to famous projects by established artists and programmers.

Runme.org is structured in two major ways: taxonomically/rationally (category list) and intuitively (keyword cloud).

The best works submitted to Runme.org will be reviewed by the "experts", who will change over time.

Though Runme.org partly grew from the Read_me 1.2 festival, it is an autonomous repository upon which the festival is now based.

The second edition of Read_Me festival took place in Helsinki in May 2003.

Runme.org is a collaborative and open project that was developed by Amy Alexander, Florian Cramer, Matthew Fuller, Olga Goriunova, Thomax Kaulmann, Alex McLean, Pit Schultz, Alexei Shulgin, and The Yes Men. In summer 2003 Hans Bernhard and Alessandro Ludovico have joined the expert team."

<< preface

it is also meant to be an additional resource of information and recommended reading for my students of the prehystories of new media class that i teach at the school of the art institute of chicago in fall 2008.

the focus is on the time period from the beginning of the 20th century up to today.

>> search this blog

2008-07-15

>> runme.org

Gepostet von

Nina Wenhart ...

hh:mm

5:46 PM

0

replies

tags -

artistic software,

code art

![]()

Bookmark this post:blogger tutorials

Social Bookmarking Blogger Widget |

>> Guy Debord, "Introduction to a Critique of Urban Geography "

Of all the affairs we participate in, with or without interest, the groping search for a new way of life is the only aspect still impassioning. Aesthetic and other disciplines have proved blatantly inadequate in this regard and merit the greatest detachment. We should therefore delineate some provisional terrains of observation, including the observation of certain processes of chance and predictability in the streets.

The word psychogeography, suggested by an illiterate Kabyle as a general term for the phenomena a few of us were investigating around the summer of 1953, is not too inappropriate. It does not contradict the materialist perspective of the conditioning of life and thought by objective nature. Geography, for example, deals with the determinant action of general natural forces, such as soil composition or climatic conditions, on the economic structures of a society, and thus on the corresponding conception that such a society can have of the world. Psychogeography could set for itself the study of the precise laws and specific effects of the geographical environment, consciously organized or not, on the emotions and behavior of individuals. The adjective psychogeographical, retaining a rather pleasing vagueness, can thus be applied to the findings arrived at by this type of investigation, to their influence on human feelings, and even more generally to any situation or conduct that seems to reflect the same s pirit of discovery.

It has long been said that the desert is monotheistic. Is it illogical or devoid of interest to observe that the district in Paris between Place de la Contrescarpe and Rue de l'Arbal? conduces rather to atheism, to oblivion and to the disorientation of habitual reflexes?

The notion of utilitariness should be situated historically. The concern to have open spaces allowing for the rapid circulation of troops and the use of artillery against insurrections was at the origin of the urban renewal plan adopted by the Second Empire. But from any standpoint other than that of police control, Haussmann's Paris is a city built by an idiot, full of sound and fury, signifying nothing. Today urbanism's main problem is ensuring the smooth circulation of a rapidly increasing quantity of motor vehicles. We might be justified in thinking that a future urbanism will also apply itself to no less utilitarian projects that will give the greatest consideration to psychogeographical possibilities.

This present abundance of private cars is nothing but the result of the constant propaganda by which capitalist production persuades the masses--and this case is one of its most astonishing successes--that the possession of a car is one of the privileges our society reserves for its privileged members. (At the same time, anarchical progress negates itself: one can thus savor the spectacle of a prefect of police urging Parisian car owners to use public transportation.)

We know with what blind fury so many unprivileged people are ready to defend their mediocre advantages. Such pathetic illusions of privilege are linked to a general idea of happiness prevalent among the bourgeoisie and maintained by a system of publicity that includes Malraux's aesthetics as well as the imperatives of Coca-Cola--an idea of happiness whose crisis must be provoked on every occasion by every means.

The first of these means are undoubtedly the systematic provocative dissemination of a host of proposals tending to turn the whole of life into an exciting game, and the continual depreciation of all current diversions--to the extent, of course, that they cannot be detourned to serve in constructions of more interesting ambiances. The greatest difficulty in such an undertaking is to convey through these apparently delirious proposals a sufficient degree of serious seduction. To accomplish this we can imagine an adroit use of currently popular means of communication. But a disruptive sort of abstention, or manifestations designed to radically frustrate the fans of these means of communication, could also promote at little expense an atmosphere of uneasiness extremely favorable for the introduction of a few new notions of pleasure.

This idea, that the realization of a chosen emotional situation depends only on the thorough understanding and calculated application of a certain number of concrete techniques, inspired this "Psychogeographical Game of the Week" published, not without a certain humor, in Potlatch #1:

"In accordance with what you are seeking, choose a country, a more or less populated city, a more or less busy street. Build a house. Furnish it. Use decorations and surroundings to the best advantage. Choose the season and the time of day. Bring together the most suitable people, with appropriate records and drinks. The lighting and the conversation should obviously be suited to the occasion, as should be the weather or your memories.

"If there has been no error in your calculations, the result should satisfy you."

We need to work toward flooding the market--even if for the moment merely the intellectual market--with a mass of desires whose realization is not beyond the capacity of man's present means of action on the material world, but only beyond the capacity of the old social organization. It is thus not without political interest to publicly counterpose such desires to the elementary desires that are endlessly rehashed by the film industry and in psychological novels like those of that old hack Mauriac. ("In a society based on poverty, the poorest products are inevitably used by the greatest number," Marx explained to poor Proudhon.)

The revolutionary transformation of the world, of all aspects of the world, will confirm all the dreams of abundance. The sudden change of ambiance in a street within the space of a few meters; the evident division of a city into zones of distinct psychic atmospheres; the path of least resistance which is automatically followed in aimless strolls (and which has no relation to the physical contour of the ground); the appealing or repelling character of certain places--all this seems to be neglected. In any case it is never envisaged as depending on causes that can be uncovered by careful analysis turned to account. People are quite aware that some neighborhoods are sad and others pleasant. But they generally simply assume elegant streets cause a feeling of satisfaction and that poor street are depressing, and let it go at that. In fact, the variety of possible combinations of ambiances, analogous to the blending of pure chemicals in an infinite number of mixtures, gives rise to feelings as differentiated and complex as any other form of spectacle can evoke. The slightest demystified investigation reveals that the qualitatively or quantitatively different influences of diverse urban decors cannot be determined solely on the basis of the era or architectural style, much less on the basis of housing conditions.

The research that we are thus led to undertake on the arrangement of the elements of the urban setting, in close relation with the sensations they provoke, entails bold hypotheses that must constantly corrected in the light of experience, by critique and self-critique.

Certain of Chirico's paintings, which are clearly provoked by architecturally originated sensations, exert in turn an effect on their objective base to the point of transforming it: they tend themselves to become blueprints or models. Disquieting neighborhoods of arcades could one day carry on and fulfill the allure of these works.

I scarcely know of anything but those two harbors at dusk painted by Claude Lorrain--which are at the Louvre and which juxtapose extremely dissimilar urban ambiances--that can rival in beauty the Paris metro maps. It will be understood that in speaking here of beauty I don't have in mind plastic beauty--the new beauty can only be beauty of situation--but simply the particularly moving presentation, in both cases, of a sum of possibilities.

Among various more difficult means of intervention, a renovated cartography seems appropriate for immediate utilization.

The production of psychogeographic maps, or even the introduction of alterations such as more or less arbitrarily transposing maps of two different regions, can contribute to clarifying certain wanderings that express not subordination to randomness but complete insubordination to habitual influences (influences generally categorized as tourism that popular drug as repugnant as sports or buying on credit). A friend recently told me that he had just wandered through the Harz region of Germany while blindly following the directions of a map of London This sort of game is obviously only a mediocre beginning in comparison to the complete construction of architecture and urbanism that will someday be within the power of everyone. Meanwhile we can distinguish several stages of partial, less difficult realizations, beginning with the mere displacement of elements of decoration from the locations where we are used to seeing them.

For example, in the preceding issue of this journal Marien proposed that when global resources have ceased to be squandered on the irrational enterprises that are imposed on us today, all the equestrian statues of all the cities of the world be assembled in a single desert. This would offer to the passersby--the future belongs to them--the spectacle of an artificial cavalry charge, which could even be dedicated to the memory of the greatest massacrers of history, from Tamerlane to Ridgway. Here we see reappear one of the main demands of this generation: educative value.

In fact, there is nothing to be expected until the masses in action awaken to the conditions that are imposed on them in all domains of life, and to the practical means of changing them.

"The imaginary is that which tends to become real," wrote an author whose name, on account of his notorious intellectual degradation, I have since forgotten. The involuntary restrictiveness of such a statement could serve as a touchstone exposing various farcical literary revolutions: That which tends to remain unreal is empty babble.

Life, for which we are responsible, encounters, at the same time as great motives for discouragement, innumerable more or less vulgar diversions and compensations. A year doesn't go by when people we loved haven't succumbed, for lack of having clearly grasped the present possibilities, to some glaring capitulation. But the enemy camp objectively condemns people to imbecility and already numbers millions of imbeciles; the addition of a few more makes no difference. The first moral deficiency remains indulgence, in all its forms.

Gepostet von

Nina Wenhart ...

hh:mm

5:32 PM

0

replies

tags -

situationists,

text

![]()

Bookmark this post:blogger tutorials

Social Bookmarking Blogger Widget |

>> Guy Debord, "A Theory of the Dérive", 1956

from: http://library.nothingness.org/articles/all/all/display/314

One of the basic situationist practices is the dérive [literally: “drifting”], a technique of rapid passage through varied ambiances. Dérives involve playful-constructive behavior and awareness of psychogeographical effects, and are thus quite different from the classic notions of journey or stroll.

In a dérive one or more persons during a certain period drop their relations, their work and leisure activities, and all their other usual motives for movement and action, and let themselves be drawn by the attractions of the terrain and the encounters they find there. Chance is a less important factor in this activity than one might think: from a dérive point of view cities have psychogeographical contours, with constant currents, fixed points and vortexes that strongly discourage entry into or exit from certain zones.

But the dérive includes both this letting-go and its necessary contradiction: the domination of psychogeographical variations by the knowledge and calculation of their possibilities. In this latter regard, ecological science — despite the narrow social space to which it limits itself — provides psychogeography with abundant data.

The ecological analysis of the absolute or relative character of fissures in the urban network, of the role of microclimates, of distinct neighborhoods with no relation to administrative boundaries, and above all of the dominating action of centers of attraction, must be utilized and completed by psychogeographical methods. The objective passional terrain of the dérive must be defined in accordance both with its own logic and with its relations with social morphology.

In his study Paris et l’agglomération parisienne (Bibliothèque de Sociologie Contemporaine, P.U.F., 1952) Chombart de Lauwe notes that “an urban neighborhood is determined not only by geographical and economic factors, but also by the image that its inhabitants and those of other neighborhoods have of it.” In the same work, in order to illustrate “the narrowness of the real Paris in which each individual lives . . . within a geographical area whose radius is extremely small,” he diagrams all the movements made in the space of one year by a student living in the 16th Arrondissement. Her itinerary forms a small triangle with no significant deviations, the three apexes of which are the School of Political Sciences, her residence and that of her piano teacher.

Such data — examples of a modern poetry capable of provoking sharp emotional reactions (in this particular case, outrage at the fact that anyone’s life can be so pathetically limited) — or even Burgess’s theory of Chicago’s social activities as being distributed in distinct concentric zones, will undoubtedly prove useful in developing dérives.

If chance plays an important role in dérives this is because the methodology of psychogeographical observation is still in its infancy. But the action of chance is naturally conservative and in a new setting tends to reduce everything to habit or to an alternation between a limited number of variants. Progress means breaking through fields where chance holds sway by creating new conditions more favorable to our purposes. We can say, then, that the randomness of a dérive is fundamentally different from that of the stroll, but also that the first psychogeographical attractions discovered by dérivers may tend to fixate them around new habitual axes, to which they will constantly be drawn back.

An insufficient awareness of the limitations of chance, and of its inevitably reactionary effects, condemned to a dismal failure the famous aimless wandering attempted in 1923 by four surrealists, beginning from a town chosen by lot: Wandering in open country is naturally depressing, and the interventions of chance are poorer there than anywhere else. But this mindlessness is pushed much further by a certain Pierre Vendryes (in Médium, May 1954), who thinks he can relate this anecdote to various probability experiments, on the ground that they all supposedly involve the same sort of antideterminist liberation. He gives as an example the random distribution of tadpoles in a circular aquarium, adding, significantly, “It is necessary, of course, that such a population be subject to no external guiding influence.” From that perspective, the tadpoles could be considered more spontaneously liberated than the surrealists, since they have the advantage of being “as stripped as possible of intelligence, sociability and sexuality,” and are thus “truly independent from one another.”

At the opposite pole from such imbecilities, the primarily urban character of the dérive, in its element in the great industrially transformed cities — those centers of possibilities and meanings — could be expressed in Marx’s phrase: “Men can see nothing around them that is not their own image; everything speaks to them of themselves. Their very landscape is alive.”

One can dérive alone, but all indications are that the most fruitful numerical arrangement consists of several small groups of two or three people who have reached the same level of awareness, since cross-checking these different groups’ impressions makes it possible to arrive at more objective conclusions. It is preferable for the composition of these groups to change from one dérive to another. With more than four or five participants, the specifically dérive character rapidly diminishes, and in any case it is impossible for there to be more than ten or twelve people without the dérive fragmenting into several simultaneous dérives. The practice of such subdivision is in fact of great interest, but the difficulties it entails have so far prevented it from being organized on a sufficient scale.

The average duration of a dérive is one day, considered as the time between two periods of sleep. The starting and ending times have no necessary relation to the solar day, but it should be noted that the last hours of the night are generally unsuitable for dérives.

But this duration is merely a statistical average. For one thing, a dérive rarely occurs in its pure form: it is difficult for the participants to avoid setting aside an hour or two at the beginning or end of the day for taking care of banal tasks; and toward the end of the day fatigue tends to encourage such an abandonment. But more importantly, a dérive often takes place within a deliberately limited period of a few hours, or even fortuitously during fairly brief moments; or it may last for several days without interruption. In spite of the cessations imposed by the need for sleep, certain dérives of a sufficient intensity have been sustained for three or four days, or even longer. It is true that in the case of a series of dérives over a rather long period of time it is almost impossible to determine precisely when the state of mind peculiar to one dérive gives way to that of another. One sequence of dérives was pursued without notable interruption for around two months. Such an experience gives rise to new objective conditions of behavior that bring about the disappearance of a good number of the old ones.[1]

The influence of weather on dérives, although real, is a significant factor only in the case of prolonged rains, which make them virtually impossible. But storms or other types of precipitation are rather favorable for dérives.

The spatial field of a dérive may be precisely delimited or vague, depending on whether the goal is to study a terrain or to emotionally disorient oneself. It should not be forgotten that these two aspects of dérives overlap in so many ways that it is impossible to isolate one of them in a pure state. But the use of taxis, for example, can provide a clear enough dividing line: If in the course of a dérive one takes a taxi, either to get to a specific destination or simply to move, say, twenty minutes to the west, one is concerned primarily with a personal trip outside one’s usual surroundings. If, on the other hand, one sticks to the direct exploration of a particular terrain, one is concentrating primarily on research for a psychogeographical urbanism.

In every case the spatial field depends first of all on the point of departure — the residence of the solo dériver or the meeting place selected by a group. The maximum area of this spatial field does not extend beyond the entirety of a large city and its suburbs. At its minimum it can be limited to a small self-contained ambiance: a single neighborhood or even a single block of houses if it’s interesting enough (the extreme case being a static-dérive of an entire day within the Saint-Lazare train station).

The exploration of a fixed spatial field entails establishing bases and calculating directions of penetration. It is here that the study of maps comes in — ordinary ones as well as ecological and psychogeographical ones — along with their correction and improvement. It should go without saying that we are not at all interested in any mere exoticism that may arise from the fact that one is exploring a neighborhood for the first time. Besides its unimportance, this aspect of the problem is completely subjective and soon fades away.

In the “possible rendezvous,” on the other hand, the element of exploration is minimal in comparison with that of behavioral disorientation. The subject is invited to come alone to a certain place at a specified time. He is freed from the bothersome obligations of the ordinary rendezvous since there is no one to wait for. But since this “possible rendezvous” has brought him without warning to a place he may or may not know, he observes the surroundings. It may be that the same spot has been specified for a “possible rendezvous” for someone else whose identity he has no way of knowing. Since he may never even have seen the other person before, he will be encouraged to start up conversations with various passersby. He may meet no one, or he may even by chance meet the person who has arranged the “possible rendezvous.” In any case, particularly if the time and place have been well chosen, his use of time will take an unexpected turn. He may even telephone someone else who doesn’t know where the first “possible rendezvous” has taken him, in order to ask for another one to be specified. One can see the virtually unlimited resources of this pastime.

Our loose lifestyle and even certain amusements considered dubious that have always been enjoyed among our entourage — slipping by night into houses undergoing demolition, hitchhiking nonstop and without destination through Paris during a transportation strike in the name of adding to the confusion, wandering in subterranean catacombs forbidden to the public, etc. — are expressions of a more general sensibility which is no different from that of the dérive. Written descriptions can be no more than passwords to this great game.

The lessons drawn from dérives enable us to draw up the first surveys of the psychogeographical articulations of a modern city. Beyond the discovery of unities of ambiance, of their main components and their spatial localization, one comes to perceive their principal axes of passage, their exits and their defenses. One arrives at the central hypothesis of the existence of psychogeographical pivotal points. One measures the distances that actually separate two regions of a city, distances that may have little relation with the physical distance between them. With the aid of old maps, aerial photographs and experimental dérives, one can draw up hitherto lacking maps of influences, maps whose inevitable imprecision at this early stage is no worse than that of the first navigational charts. The only difference is that it is no longer a matter of precisely delineating stable continents, but of changing architecture and urbanism.

Today the different unities of atmosphere and of dwellings are not precisely marked off, but are surrounded by more or less extended and indistinct bordering regions. The most general change that dérive experience leads to proposing is the constant diminution of these border regions, up to the point of their complete suppression.

Within architecture itself, the taste for dériving tends to promote all sorts of new forms of labyrinths made possible by modern techniques of construction. Thus in March 1955 the press reported the construction in New York of a building in which one can see the first signs of an opportunity to dérive inside an apartment:

“The apartments of the helicoidal building will be shaped like slices of cake. One will be able to enlarge or reduce them by shifting movable partitions. The half-floor gradations avoid limiting the number of rooms, since the tenant can request the use of the adjacent section on either upper or lower levels. With this setup three four-room apartments can be transformed into one twelve-room apartment in less than six hours.”

(To be continued.)

Gepostet von

Nina Wenhart ...

hh:mm

5:30 PM

0

replies

tags -

situationists,

text,

theory

![]()

Bookmark this post:blogger tutorials

Social Bookmarking Blogger Widget |

>> exhibition;: "This is Tomorrow", 1956

the complete catalogue can be found here: http://www.thisistomorrow2.com/images/cat_1956/cat_web/FrameSet.htm

the complete catalogue can be found here: http://www.thisistomorrow2.com/images/cat_1956/cat_web/FrameSet.htm

from: www.independentgroup.org.uk/.../

Hamilton’s most famous exhibition contribution was This is Tomorrow. He designed the space with John McHale and John Voelcker and its theme was problems of perception. It included a giant cut-out of Marilyn Monroe and Robbie the Robot – the latter borrowed from the opening of the film The Forbidden Planet – and a juke box. Each of the twelve groups involved with the exhibition designed a poster, and Hamilton designed Group 2’s, using a collage image that would be destined to become emblematic of 1950s, American consumer culture, Just What Is It That Makes Today’s Homes So Different, So Appealing?

from: http://www.thisistomorrow2.com/pages_gb/1956gb.html

This is Tomorrow has become an iconic exhibition notable not only for the arrival of the naming of Pop Art but also as a captured moment for the multi-disciplinary merging of the disciplines of art and architecture

"In 'This is Tomorrow' the visitor is exposed to space effects, play with signs, a wide range of materials and structures, which, taken together make of art and architecture a many chanelled activity, as far from ideal standards as the street outside". --- Lawrence ALLOWAY, introduction, Exhibition Catalogue

From: "orthodox abstract art, with its classical regularity and rational order, through room-size sculptures to walk through, to crazy-house structures plastered with pin-up images from the popular press." --- press release, This is Tomorrow 1956

Gepostet von

Nina Wenhart ...

hh:mm

4:42 PM

0

replies

tags -

catalogue,

early exhibitions,

early new media

![]()

Bookmark this post:blogger tutorials

Social Bookmarking Blogger Widget |

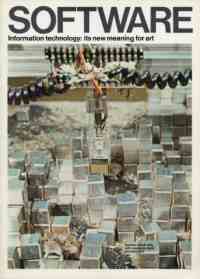

>> exhibition: Jack Burnham, "Software", 1970

Gepostet von

Nina Wenhart ...

hh:mm

4:40 PM

0

replies

tags -

code art,

concept art,

early exhibitions,

early new media,

minimalism

![]()

Bookmark this post:blogger tutorials

Social Bookmarking Blogger Widget |

>> Robert Mallary, "Notes on Jack Burnham's Concepts of a Software Exhibition", 1970

from: Leonardo, Vol. 3, pp. 189-190. Pergamon Press 1970. Printed in Great Britain

Jack Burnham has been receiving, in my view, the recognition he deserves for his efforts to draw attention to the impact of cybernetics, general systems theory and computers on contemporary art. My own respect for Burnham is attested to by references to his book, Beyond Modern Sculpture, in my article 'Computer Sculpture: Six Levels of Cybernetics', Artforum (May 1969) and by my discussion of his work at a session of the International Cybernetics Congress held in London in September 1969. Recently, in a communication to the New York Review, Burnham defined his central premise as '... we are moving from an art centered upon objects to one focused upon systems, thus implying that sculptured objects are in eclipse'. In a statement explaining the scope of a 'Software' exhibition he has proposed for the Jewish Museum in New York (tentatively scheduled for late spring, 1970), he made his point even more explicitly by writing 'If the "Software" exhibit is to be successful in emphasizing the nature of electronically supported software, it should then remove the traditional hardware props of art from the eye of the viewer, mainly those vestiges of painting and sculpture'. In this same statement he defined electronically supported software as 'radio, telephone, telephone photo- copying, television, microcard library information systems, teletype and teaching machines'. These quotes make clear what Burnham means by software, though, to my knowledge, he has yet to define precisely what he means by 'systems art', except in the negative sense of repudiating the sculptural object. One can only surmise that his thinking accords more with what we have come to know as 'concept art' and related tendencies, rather than with cybernetics and general systems theory. What he has done in fact, is draw upon the prestige of these disciplines (and some of the vocabulary) to blur the distinction between art as a particular kind of immediate, sensory experience and the process of dealing with it on various levels of abstraction- apparently failing to realize that in both cybernetics and general systems theory it is normal to distinguish between the abstract model and the real-world system it is intended to represent. Burnham's more puzzling mistake, however, lies in his gross misunderstanding of the word software, or at least in his gross misuse of it, and his resort to such a misleading expression as 'electronically supported software'-as if hardware normally supports software, instead of the other way round [1]. This is a surprising choice because Burnham must have learned enough about computers by this time to know that software refers to programming input for the computer-the term having been derived from the use of punched cards and paper tape for this purpose. It is legitimate to speak of software as output if the program generates another program which in turn becomes a second input of the computer. While Burnham is not alone in his abuse of a perfectly good word such as software (e.g. in audio- visual education, slides and films are sometimes referred to as software and the projectors as hardware) there is more involved than mere quibbling over terminology. A large computer, supported by appropriate software, is a general, all-purpose device capable of performing a host of diverse functions. In effect, it is the software that makes the difference. Furthermore, software constitutes roughly half of the overhead costs of the computer industry. Its meaning, therefore, is too specific, too useful and too important to be used in connection with something as distinct and important in its own right as printed and graphic output. which is normally referred to as hard copy. To use software in describing a television image and the acoustical output from a radio or a telephone, is to drain the word of almost any meaning. It is also puzzling why Burnham, with his almost Manichean antiphysicalism and his bias against hardware, would thus limit the possibilities of cybernetic and systems art. Drawing upon computer terminology, it might even make sense to define sculpture as a shifting interface between the spiritual and the physical. In any event, the profound enigma and ambiguity involved in the conjunction of the physical and psychological aspects of sculpture are (for me, at least) one of its greatest attractions. I see no reason why this aspect of the art should not be refreshed and renewed on a higher technological and systems level. Astronauts are walking about on the Moon because software and hardware are brought together as integrated systems, so why should not cybernetic art benefit from the same approach ? Why should artists avoid either software or hardware? Why should not cybernetic art be experienced variously as objects, functions, processes-including conceptual processes-and combinations of these? I am not suggesting that the title of the exhibition be changed from 'Software' to 'Hard Copy' because, despite the label, there is a good chance of its turning out to be an interesting and important event, which will do much to stimulate interest in cybernetic and systems art. Even if the show fails in this or fails to provide us with good examples of 'systems' art, perhaps it will compel Burnham to give us a better idea of what he means by the phrase. In the statement already quoted, Burnham also wrote: 'Some of this educational background will be given in the catalogue but a more important approach will be to build this information into the exhibition as a mixed-media presentation'. This suggests that the exhibition itself may prove to be an example of what Burnham means by 'systems art'. It seems likely that it will turn out to be one of those new kinds of exhibitions in which the 'medium is the message'. An exhibition which, as an integrated entity, is itself the real system, with the individual displays functioning as so many cogwheels, i.e. as subsystems within the exhibition's global scheme.

REFERENCES 1. Terminology, Leonardo 3, 97 (1970). Mr. Burnham's comments on Mr. Mallary's notes will be found in the Letters section of this issue of Leonardo -THE EDITOR. 190

Gepostet von

Nina Wenhart ...

hh:mm

4:24 PM

0

replies

tags -

early exhibitions,

review,

text

![]()

Bookmark this post:blogger tutorials

Social Bookmarking Blogger Widget |

>> Brian Holmes, "Escape the Overcode", 2006

info (from joncates):

Escape the Overcode - Brian Holmes (2006)is a presentation by Brian Holmes on Cybernetics in jonCates' Prehistories of New Media course at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago.

Gepostet von

Nina Wenhart ...

hh:mm

4:04 PM

0

replies

tags -

cybernetics,

lecture

![]()

Bookmark this post:blogger tutorials

Social Bookmarking Blogger Widget |

>> Edward Shanken, "The House That Jack Built: Jack Burnham's Concept of 'Software' as a Metaphor for Art ", 1998

from: http://www.artexetra.com/House.html

- Published by Leonardo Electronic Almanac 6:10 (November, 1998)

Reprinted in Roy Ascott, ed., Reframing Consciousness: Art and Consciousness in the Post-Biological Era. Exeter: Intellect, 1999. This research is a portion of the author's doctoral dissertation in Art History, and was supported in part by a Luce/ACLS dissertation fellowship inAmerican art.

Abstract: This paper identifies and analyzes the convergence of computers, experimental art practice, and structuralist theory in Jack Burnham's Software exhibition at the Jewish Museum. In contrast to the numerous art and technology exhibitions which took place between 1966-1972, and which focused on the aesthetic applications of technological apparatus, Software was predicated on theÝidea of "software" as a metaphor for art. Under this rubric, the curator explored his notion of the mythic structure of art, and its convergence with information technology, and the increasing conceptualism of art in the late 1960s. I suggest that these components represent the interlocked emergence of postmodernity at this critical art historical moment.

Jack Burnham's first book, Beyond Modern Sculpture: The Effects of Science and Technology on the Sculpture of Our Time, 1968, established him as the pre-eminent champion of art and technology of his generation. Building on this foundation, his second book, The Structure of Art, 1971, developed one of the first systematic methods for applying structural analysis to the interpretation of individual artworks as well as to the canon of western art history itself. Many of his articles for Arts magazine from 1968-70, where he was Associate Editor (1972-76) and Artforum from 1971-3, where he was Contributing Editor (1971-2), were collected in his third book, The Great Western Salt Works, 1973. These essays still remain amongst the most insightful commentaries on conceptual art, already suggesting what he now sees in retrospect as the "great hiatus between standard modernism and postmodernism."[3]

In 1970, at the invitation of Jewish Museum director, Karl Katz, Burnham curated Software, the only major show he has curated to date. In contrast to the numerous art and technology exhibitions which took place between 1966-1972, and which focused on the aesthetic applications of technological apparatus, Software was predicated on the ideas of "software" and "information technology" as metaphors for art. He conceived of "software" as parallel to the aesthetic principles, concepts, or programs that underlie the formal embodiment of the actual art objects, which in turn parallel "hardware." In this regard, he interpreted "Post-Formalist Art" (his term referring to experimental art practices including performance, interactive art, and especially conceptual art) as predominantly concerned with the software aspect of aesthetic production.

It is significant that Burnham organized Software while writing The Structure of Art and conceived of the show, in part, as a concrete realization of his structuralist art theories. Drawing on Claude Levi-Strauss's idea that cultural institutions are mythic structures that emerge differentially from universal principles, Burnham theorized that western art constituted a mythic structure. And he theorized that the primary project of conceptual art was to question and lay bare the mythic structure of art, demystifying art and revealing it for what its internal logic.[4]

Such ideas were already present in Burnham's 1970 article "Alice's Head." True to the title, he began the essay - which focused on the work of conceptual artists Joseph Kosuth, Douglas Huebler, Robert Barry, Lawrence Wiener, and Les Levine - with the following quote from Lewis Carroll's Alice in Wonderland:

"...'Well! I've often seen a cat without a grin,' thought Alice, 'but a grin without a cat! It's the most curious thing I ever saw in all my life!'"[5]By selecting for his preamble Alice's curiosity over a disembodied presence, Burnham suggested that, like a grin without a cat, a work of conceptual art is all but devoid of the material trappings of paint or marble traditionally associated with art objects. Similarly, he explained Software as "an attempt to produce aesthetic sensations without the intervening 'object;' in fact, to exacerbate the conflict or sense of aesthetic tension by placing works in mundane, non-art formats."[6]

Burnham directly interacted with computer software when he was a Fellow at the Center for Advanced Visual Studies under Gyorgy Kepes at MIT during the 1968-9 academic year. Having received his MFA from Yale in 1961, he was invited, as an artist, "to learn to use the time- sharing computer system at MIT's Lincoln Laboratories." In a paper entitled "The Aesthetics of Intelligent Systems" delivered at the Guggenheim Museum in 1969, Burnham discussed this experience of working with computers, comparing the brain and the computer as information processing systems, and drawing further parallels between information processing and conceptual art. He stated, moreover, that "the aesthetic implications of a technology become manifest only when it becomes pervasively, if not subconsciously, present in the life-style of a culture," and claimed that "present social circumstances point in that direction."[7]

As Burnham explained in the paper, given the artistic limits of the computer system at his disposal, he focused on the "challenge of ... discovering a program's memory, interactive ability, and logic functions," and on " gradually... conceptualiz[ing] an entirely abstract model of the program." In this regard, he was especially interested in how "a dialogue evolves between the participants - the computer program and the human subject - so that both move beyond their original state." Clearly he recognized how his interaction with software altered his own consciousness, which in turn simultaneously altered the program. Finally, he drew a parallel between this sort of two-way communication, and the "eventual two-way communication in art." In 1969, he wrote,

The computer's most profound aesthetic implication is that we are being forced to dismiss the classical view of art and reality which insists that man stand outside of reality in order to observe it, and, in art, requires the presence of the picture frame and the sculpture pedestal. The notion that art can be separated from its everyday environment is a cultural fixation [in other words, a mythic structure] as is the ideal of objectivity in science. It may be that the computer will negate the need for such an illusion by fusing both observer and observed, "inside" and "outside." It has already been observed that the everyday world is rapidly assuming identity with the condition of art.[8]The metaphorical premise of Software permitted Burnham to explore convergences between his notion of the mythic structure of art, emerging information technology, and the increasing conceptualism characteristic of much experimental art in the late 1960's. These components were conjoined in works that emulated the sort of two-way communication he experienced with computer programs and which he advocated in art. The catalog emphasized the importance of creating a context in which "the public can personally respond to programmatic situations structured by artists," and explicitly stated that the show "makes no distinctions between art and non-art."

Burnham was careful to select works of art that demonstrated his theories. I contend that many of these works anticipated and participated in important trends in subsequent intellectual and cultural history. In this sense they contributed to the transformation of consciousness. Quoting McLuhan, Burnham identified this shift from the "isolation and domination of society by the visual sense" defined and limited by one-point perspective, to a way of thinking about the world based on the interactive feedback of information amongst systems and their components in global fields, in which there is "no logical separation between the mind of the perceiver and the environment."[10]

For example, in the hypertext system, "Labyrinth," a collaboration between Xanadu creator Ted Nelson and programmer Ned Woodman, users could obtain information from an "interactive catalog" of the exhibition by choosing their own narrative paths through an interlinked database of texts, then receive a print-out of their particular "user history." The self-constructed, non-linear unfolding of Labyrinth shares affinities with structuralist critiques of authorship, narrative structure, and "writerly" (as opposed to "readerly") texts, made by Barthes. Needless to say, with the advent of powerful Internet browsers like Netscape, and the proliferation of CD-ROM technology, the decentered and decentering quality of hypertext has become the subject (and method) of a growing critical post-structuralist literature, and arguably a central icon of postmodernity. It should be noted that this first public exhibition of a hypertext system occurred, and this was perhaps not just a coincidence, in the context of experimental art.

Hans Haacke's "Visitor's Profile" encouraged visitors to interact with a computer by inputting personal information, which was then tabulated to output statistical data on the exhibition's audience. Such demographic research - as art - opened up a critical discourse, following Foucault and others, on the exclusivity of cultural institutions and their patrons, revealing the myth of public service as a thin veneer justifying the hierarchical values that reify extant social relations. Similarly, "Interactive Paper Systems" by Sonia Sheridan, engaged museum- goers in a creative exchange with the artist and 3M's first commercially available color photocopying machine, dissolving conventional artist-viewer-object relations. In "The Seventh Investigation (Art as Idea as Idea)" Joseph Kosuth utilized multiple forms of mass media and distribution (a billboard, an newspaper advertisement, a banner, and a museum installation) to question the conceptual and contextual boundaries between art, philosophy, commerce, pictures, and texts.

In works such as these, the relationship Burnham intuited between experimental art practices and "art and technology" problematized conventional distinctions between them, and offered important insights into the complementarity of conventional, experimental, and electronic media in the emerging cultural paradigm later theorized as postmodernity. In this regard, Levi- Strauss's models from structural anthropology, along with Thomas Kuhn's critique of the history of science, led Burnham to question what he saw as the structural foundations of art history's narrative of progressive and discrete movements, a critique he elaborated in The Structure of Art.

As a final example, Nicholas Negroponte and the Architecture Machine Group (precursor to the MIT Media Lab, which Negroponte now directs) submitted "Seek," a computer-controlled robotic environment that, at least in theory, cybernetically reconfigured itself in response to the behavior of the gerbils that inhabited it. I interpret Seek as an early example of "intelligent architecture," a growing concern of the design community internationally.[11] By synthesizing cybernetics, aesthetics, phenomenology, and semiotics, Software emphasized the process of audience interaction with "control and communication techniques," encouraging the "public" to "personally respond" and ascribe meaning to experience. In so doing, Software questioned the intrinsic significance of objects and implied that meaning emerges from perception in what Burnham (quoting Barthes) later identified as "syntagmatic" and "systematic" contexts.[12]

A further abiding metaphor in Burnham's concept for Software was Marcel Duchamp's Large Glass, 1915-22, which served as an architectural model for the actual installation. Burnham described the relationship of Software to Duchamp's magnum opus in a 1970 interview with Willoughby Sharp. Iconographically, he explained, the Large Glass,

has a lot of machines in the lower section - scissors, grinders, gliders, etc... it represents the patriarchal element, the elements of reason, progress, male dominance. The top of [it] is the female component: intuition, love, internal consistency, art, beauty, and myth itself.[13]Burnham claimed that "Duchamp was trying to establish that artists, in their lust to produce art, to ravish art, are going to slowly undress [it] until there's nothing left, and then art is over."

He then went on to reveal Software's organizational logic:

As a kind of personal joke... I tried to recreate the same relationships in Software. I've produced two floors of computers and experiments. Then upstairs on the third floor, conceptual art with Burgy, Huebler, Kosuth, and others, which to my mind represents the last intelligent gasp of the art impulse.Burnham's point, following his interpretation of Duchamp, was not that art was dead, or dying, or about to dissolve into nothingness. Rather, he believed that art was "dissolving into comprehension." He claimed that conceptual art was playing an important role in that process, by "feeding off the logical structure of art itself..., taking a piece of information and reproducing it as both a signified and a signifier." In other words, such work explicitly identified the signifying codes which define the mythic structure of art. Instead of simply obeying or transgressing those codes, it appropriated them as motifs, as signifiers, thereby demystifying the protocols by which meaning and value have conventionally been produced in art.

In this regard, Burnham became very critical of the role of emerging technology in art.[14] Having lost faith in its ability to contribute in a meaningful way to the signifying system that he believed to mediate the mythic structure of western art, in Software he purposely joined the nearly absent forms of conceptual art with the mechanical forms of technological non-art to "exacerbate the conflict or sense of aesthetic tension" between them.[15] Given his interpretation of Duchamp, such a gesture also can be seen as an attempt to deconstruct the categorical oppositions of art and non-art by revealing their semiotic similarity as information processing systems.

I would be remiss if I did not mention that in many respects Software was a disaster. The DEC PDP-8 Time Share Computer that controlled many of the works did not function for the first month of the exhibition due to problems with, ironically enough, the software. The gerbils in SEEK attacked each other, a film was destroyed by its editors, and several aspects of the exhibition - including the catalog - were censored by the Board of Trustees of the museum. The show went greatly over budget which put the Jewish Museum in a precarious position financially. The Jewish Theological Seminary bailed it out, but dictated a radical shift in the museum's mission, which precipitated Karl Katz's dismissal as its director and its demise as a leading exhibition space for experimental art. The show was scheduled to travel to the Smithsonian Institution, but that venue was canceled.Ý Many other controversies plagued Burnhamís ill-fated exhibition.[16] Nonetheless, Software remains the most conceptually and - when it worked - technologically sophisticated art and technology of the period.

Software was founded on a structuralist analysis of art in which unfolding of the history of western art evolved exclusively by a process of demythification.Ý Technology in art, for Burnham, was meaningful only to the extent it contributed to stripping away signifiers to reveal the mythic structure of art.Ý Perhaps we a getting close to a moment in which the deconstruction of artís mythic structure is approaching completion.Ý And perhaps information technology has become, as Burnhamís own theory demanded, "pervasively, if not subconsciously present in the lifestyle of [our] culture," such that its aesthetic implications are sufficiently manifest to play a constructive role in proposing new artistic paradigms.Ý The problem now confronting artists and curators involved with technology is not so much getting the machines andsoftware to work, but living up to the conceptual richness of the house that Jack built.

Ý

Notes:

[1] Burnham, J. 1970. Notes on Art and Information Processing. In Software Information Technology: Its New Meaning for Art. New York: Jewish Museum, p. 10

[2] Burnham, J. 1972. Duchamp's Bride Stripped Bare: The Meaning of the Large Glass. In Jack Burnham, Great Western Salt Works: Essays on the Meaning of Post-Formalist Art, (New York: George Braziller, 1973):Ý 116.

[3] Burnham, J. 1998.Ý Personal correspondence with the author, April 23.

[4] Burnham, J. 1973.Ý The Structure of Art.Ý New York:Ý George Braziller.

[5] Burnham J. 1973.Ý Alice's Head in Great Western Salt Works, p.Ý47.

[6] Burnham, J. 1998. Personal correspondence with the author, April 23

[7] Burnham, J. 1969. The Aesthetics of Intelligent Systems. In Fry, E. F. ed. 1970. On the Future of Art. New York: The Viking Press, p. 119. The three subsequent quotes come from same page. The "present social circumstances" to which Burnham refers here can only be the increasing pervasiveness of computer information-processing systems, which he described in the Software catalog as "the fastest growing area in this culture."

[8] Ibid, p. 103

[9] Burnham, 1970. Notes on Art and Information Processing, p. 10

[10] Burnham, 1970. Alice's Head, p. 47.

[11] See, Gerbel K. and Weibel P. eds. 1994. Intelligente Ambiente (Ars Electronica 994 catalogue). Vienna: PVS Verleger.

[12] Burnham, 1971. The Structure of Art, pp. 19-27.

[13] Sharp, W. 1970. Willoughby Sharp Interviews Jack Burnham. In Arts 45:2 (November) p. 23. All subsequent quotations are from this page.

[14] While Burnhamís loss of faith in art and technology can already be seen in his 1969 article "The Aesthetics of Intelligent Systems," op cit., his most explicit and antagonistic pronouncement against it is in Jack Burnham, "Art and Technology:Ý The Panacea that Failed" in Myths of Information:Ý Technology and Postindustrial Culture, Kathleen Woodward, ed., (Madison:Ý Coda Press, 1980); reprinted in Video Culture, John Hanhardt, ed. (New York: Visual Studies Workshop Press, 1986):Ý 232-48.

[15] Burnham, J. 1998. Personal correspondence with the author, April 23

[16] Shanken, E., 1998.Ý "Gemini Rising, Moon in Apollo:Ý Art and Technology in the US, 1966-71," in ISEA97:Ý Proceedings of the Seventh International Symposium on Electronic Art.Chicago:Ý ISEA97, 1998.

Edward A. Shanken,

Department of Art & Art History,Duke University,

Email: giftwrap@duke.edu

Gepostet von

Nina Wenhart ...

hh:mm

3:55 PM

0

replies

tags -

code art,

concept art,

early exhibitions,

exhibitions,

minimalism,

text

![]()

Bookmark this post:blogger tutorials

Social Bookmarking Blogger Widget |

>> RACTER, "The Policeman's Beard is Half Constructed", 1984

from ubuweb: http://ubu.artmob.ca/text/racter/racter_policemansbeard.pdf

Introduction

With the exception of this introduction, the writing in this book was all done by a computer. The book has been proofread for spelling but otherwise is completely unedited. The fact that a computer must somehow communicate its activities to us, and that frequently it does so by means of programmed directives in English, does suggest the possibility that we might be able to compose programming that would enable the computer to find its way around a common language "on its own" as it were. The specifics of the communication in this instance would prove of less importance than the fact that the computer was in fact communicating something. In other words, what the computer says would be secondary to the fact that it says it correctly.

Computers are supposed to compute. They are designed to accomplish in seconds (or microseconds) what humans would require years or centuries of concerted calculation effort to achieve. They are tools we employ to get certain jobs done. Bearing this in mind, the question arises: Why have a computer talk endlessly and in perfect English about nothing? Why arrange it so that no one can have prior knowledge of what it is going to say?

Why? Simply because the output generated by such programming can be fascinating, humorous, even aesthetically pleasing. Prose is the formal communication of the writer's experience, real and fancied. But, crazy as this may sound, suppose we remove that criterion: suppose we somehow arrange for the production of prose that is in no way contingent upon human experience. What would that be like? Indeed, can we even conceive of such a thing? A glance through the following pages will answer these questions.

There would appear to be a rather tedious method of generating "machine prose," which a computer could accomplish at great speed but which also might be attempted (though it would take an absurdly long time) by writing thousands of individual words and simple directives reflecting certain aspects of syntax on slips of paper, categorizing them in some systematic fashion, throwing dice to gain a random number seed, and then moving among piles of these slips of paper in a manner consistent with a set of arbitrary rules, picking a slip from Pile A, a slip from Pile B, etc., thereby composing a sentence. What actually was on the slip of paper from any given pile would be irrelevant; the rules would stipulate the pile in question. These hypothetical rules are analogous to the grammar of a language; in the case of our present program, which is called Racter, the language is English. (The name reflects a limitation of the computer on which we initially wrote the program. It only accepted file names not exceeding six characters in length. Racter seemed a reasonable foreshortening of raconteur.)

Racter, which was written in compiled BASIC on a Z80 micro with 64K of RAM, conjugates both regular and irregular verbs, prints the singular and the plural of both regular and irregular nouns, remembers the gender of nouns, and can assign variable status to randomly choosen "things." These things can be individual words, clause or sentence forms, paragraph structures, indeed whole story forms. In this way, certain aspect so the rules of English are entered into the computer. This being the case, the programmer is removed to a very great extent from the specific form of the system's output. This output is no longer a preprogrammed form. Rather, the computer forms output on its own. What the computer "forms" is dependent upon what it finds in its files, and what it can find is an extremely wide range of words that are categorized in a specific fashion and what might be called "syntax directive," which tell the computer how to string the words together. An important faculty of the program is its ability to direct the computer to maintain certain randomly chosen variables (words or phrases), which will then appear and reappear as a given block of prose is generated. This seems to spin a thread of what might initially pass for coherent thinking throughout the computer-generated copy so that once the program is run, its output is not only new and unknowable, it is apparently thoughtful. It is crazy "thinking," I grant you, but "thinking" that is expressed in perfect English.

The prose and poetry pieces have been illustrated by fanciful collages [not included in this UbuWeb edition] quite in keeping with the flavor of the computer-generated copy.

Bill ChamberlainNew York City

March 1984

Gepostet von

Nina Wenhart ...

hh:mm

2:05 PM

0

replies

tags -

artistic software,

publications,

text

![]()

Bookmark this post:blogger tutorials

Social Bookmarking Blogger Widget |

>> additional class blogs

>> labels

- Alan Turing (2)

- animation (1)

- AR (1)

- archive (14)

- Ars Electronica (4)

- art (3)

- art + technology (6)

- art + science (1)

- artificial intelligence (2)

- artificial life (3)

- artistic molecules (1)

- artistic software (21)

- artists (68)

- ASCII-Art (1)

- atom (2)

- atomium (1)

- audiofiles (4)

- augmented reality (1)

- Baby (1)

- basics (1)

- body (1)

- catalogue (3)

- CAVE (1)

- code art (23)

- cold war (2)

- collaboration (7)

- collection (1)

- computer (12)

- computer animation (15)

- computer graphics (22)

- computer history (21)

- computer programming language (11)

- computer sculpture (2)

- concept art (3)

- conceptual art (2)

- concrete poetry (1)

- conference (3)

- conferences (2)

- copy-it-right (1)

- Critical Theory (5)

- culture industry (1)

- culture jamming (1)

- curating (2)

- cut up (3)

- cybernetic art (9)

- cybernetics (10)

- cyberpunk (1)

- cyberspace (1)

- Cyborg (4)

- data mining (1)

- data visualization (1)

- definitions (7)

- dictionary (2)

- dream machine (1)

- E.A.T. (2)

- early exhibitions (22)

- early new media (42)

- engineers (3)

- exhibitions (14)

- expanded cinema (1)

- experimental music (2)

- female artists and digital media (1)

- festivals (3)

- film (3)

- fluxus (1)

- for alyor (1)

- full text (1)

- game (1)

- generative art (4)

- genetic art (3)

- glitch (1)

- glossary (1)

- GPS (1)

- graffiti (2)

- GUI (1)

- hackers and painters (1)

- hacking (7)

- hacktivism (5)

- HCI (2)

- history (23)

- hypermedia (1)

- hypertext (2)

- information theory (3)

- instructions (2)

- interactive art (9)

- internet (10)

- interview (3)

- kinetic sculpture (2)

- Labs (8)

- lecture (1)

- list (1)

- live visuals (1)

- magic (1)

- Manchester Mark 1 (1)

- manifesto (6)

- mapping (1)

- media (2)

- media archeology (1)

- media art (38)

- media theory (1)

- minimalism (3)

- mother of all demos (1)

- mouse (1)

- movie (1)

- musical scores (1)

- netart (10)

- open source (6)

- open source - against (1)

- open space (2)

- particle systems (2)

- Paul Graham (1)

- performance (4)

- phonesthesia (1)

- playlist (1)

- poetry (2)

- politics (1)

- processing (4)

- programming (9)

- projects (1)

- psychogeography (2)

- publications (36)

- quotes (2)

- radio art (1)

- re:place (1)

- real time (1)

- review (2)

- ridiculous (1)

- rotten + forgotten (8)

- sandin image processor (1)

- scientific visualization (2)

- screen-based (4)

- siggraph (1)

- situationists (4)

- slide projector (1)

- slit scan (1)

- software (5)

- software studies (2)

- Stewart Brand (1)

- surveillance (3)

- systems (1)

- tactical media (11)

- tagging (2)

- technique (1)

- technology (2)

- telecommunication (4)

- telematic art (4)

- text (58)

- theory (23)

- timeline (4)

- Turing Test (1)

- ubiquitious computing (1)

- unabomber (1)

- video (14)

- video art (5)

- video synthesizer (1)

- virtual reality (7)

- visual music (6)

- VR (1)

- Walter Benjamin (1)

- wearable computing (2)

- what is? (1)

- William's Tube (1)

- world fair (5)

- world machine (1)

- Xerox PARC (2)

>> timetravel

-

▼

08

(252)

-

▼

7

(141)

-

▼

15

(9)

- >> runme.org

- >> Guy Debord, "Introduction to a Critique of Urba...

- >> Guy Debord, "A Theory of the Dérive", 1956

- >> exhibition;: "This is Tomorrow", 1956

- >> exhibition: Jack Burnham, "Software", 1970

- >> Robert Mallary, "Notes on Jack Burnham's Concep...

- >> Brian Holmes, "Escape the Overcode", 2006

- >> Edward Shanken, "The House That Jack Built: Jac...

- >> RACTER, "The Policeman's Beard is Half Construc...

-

▼

15

(9)

-

▼

7

(141)

>> cloudy with a chance of tags

followers

.........

- Nina Wenhart ...

- ... is a Media Art historian and researcher. She holds a PhD from the University of Art and Design Linz where she works as an associate professor. Her PhD-thesis is on "Speculative Archiving and Digital Art", focusing on facial recognition and algorithmic bias. Her Master Thesis "The Grammar of New Media" was on Descriptive Metadata for Media Arts. For many years, she has been working in the field of archiving/documenting Media Art, recently at the Ludwig Boltzmann Institute for Media.Art.Research and before as the head of the Ars Electronica Futurelab's videostudio, where she created their archives and primarily worked with the archival material. She was teaching the Prehystories of New Media Class at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC) and in the Media Art Histories program at the Danube University Krems.